- INCIDENT RESPONSE PLAYBOOK

- Incident Response Process

- When to use this playbook

- Preparation Phase

- Detection & Analysis

- Containment

- Eradication & Recovery

- Post-Incident Activities

- Coordination

- Intergovernmental Coordination

INCIDENT RESPONSE PLAYBOOK

This playbook provides a standardized response process for cybersecurity incidents and describes the process and completion through the incident response phases as defined in National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800-61 Rev. 2,5 including preparation, detection and analysis, containment, eradication and recovery, and post-incident activities. This playbook describes the process FCEB agencies should follow for confirmed malicious cyber activity for which a major incident has been declared or not yet been reasonably ruled out.

Incident response can be initiated by several types of events, including but not limited to:

Automated detection systems or sensor alerts

Agency user report

Contractor or third-party ICT service provider report

Internal or external organizational component incident report or situational awareness update

Third-party reporting of network activity to known compromised infrastructure, detection of malicious code, loss of services, etc.

Analytics or hunt teams that identify potentially malicious or otherwise unauthorized activity

Incident Response Process

The incident response process starts with the declaration of the incident, as shown in Figure 1. In this context, “declaration” refers to the identification of an incident and communication to CISA and agency network defenders rather than formal declaration of a major incident as defined in applicable law and policy. Succeeding sections, which are organized by phases of the IR lifecycle, describe each step in more detail. Many activities are iterative and may continuously occur and evolve until the incident is closed out. Figure 1 illustrates incident response activities in terms of these phases, and Appendix B provides a companion checklist to track activities to completion.

When to use this playbook

Use this playbook for incidents that involve confirmed malicious cyber activity for which a major incident has been declared or not yet been reasonably ruled out.

For example:

Incidents involving lateral movement, credential access, exfiltration of data

Network intrusions involving more than one user or system

Compromised administrator accounts

This playbook does not apply to activity that does not appear to have such major incident potential, such as:

“Spills” of classified information or other incidents that are believed to result from unintentional behavior only

Users clicking on phishing emails when no compromise results

Commodity malware on a single machine or lost hardware that, in either case, is not likely to result in demonstrable harm to the national security interests, foreign relations, or economy of the United States or to the public confidence, civil liberties, or public health and safety of the American people.

5 NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-61 Rev. 2: Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

Figure 1: Incident Response Process

Figure 1: Incident Response Process

Preparation Phase

Prepare for major incidents before they occur to mitigate any impact on the organization. Preparation activities include:

Documenting and understanding policies and procedures for incident response

Instrumenting the environment to detect suspicious and malicious activity • Establishing staffing plans

Educating users on cyber threats and notification procedures

Leveraging cyber threat intelligence (CTI) to proactively identify potential malicious activity

Define baseline systems and networks before an incident occurs to understand the basics of “normal” activity. Establishing baselines enables defenders to identify deviations. Preparation also includes

Having infrastructure in place to handle complex incidents, including classified and out-of-band communications

Developing and testing courses of action (COAs) for containment and eradication

Establishing means for collecting digital forensics and other data or evidence

The goal of these items is to ensure resilient architectures and systems to maintain critical operations in a compromised state. Active defense measures that employ methods such as redirection and monitoring of adversary activities may also play a role in developing a robust incident response.6

6 For example, “Deception: Mislead, confuse, hide critical assets from, or expose covertly tainted assets to the adversary,” as defined in NIST SP 800-160 Vol. 2: Developing Cyber Resilient Systems: A Systems Security Engineering Approach.

Preparation Activities

Policies and Procedures

Document incident response plans, including processes and procedures for designating a coordination lead (incident manager). Put policies and procedures in place to escalate and report major incidents and those with impact on the agency’s mission. Document contingency plans for additional resourcing and “surge support” with assigned roles and responsibilities. Policies and plans should address notification, interaction, and evidence sharing with law enforcement.

Instrumentation

Develop and maintain an accurate picture of infrastructure (systems, networks, cloud platforms, and contractor-hosted networks) by widely implementing telemetry to support system and sensor-based detection and monitoring capabilities such as antivirus (AV) software; endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions;7 data loss prevention (DLP) capabilities; intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDPS); authorization, host, application and cloud logs;8 network flows, packet capture (PCAP); and security information and event management (SIEM) systems. Monitor for alerts generated by CISA’s EINSTEIN intrusion detection system and Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation (CDM) program to detect changes in cyber posture. Implement additional requirements for logging, log retention, and log management based on Executive Order 14028, Sec. 8. Improving the Federal Government’s Investigative and Remediation Capabilities, 9 and ensure those logs are collected centrally.

Trained Response Personnel

Ensure personnel are trained, exercised, and ready to respond to cybersecurity incidents. Train all staffing resources that may draw from in-house capabilities, available capabilities at a parent agency/department, third-party organization, or a combination thereof. Conduct regular recovery exercises to test full organizational continuity of operations plan (COOP) and failover/backup/ recovery systems to be sure these work as planned.

Cyber Threat Intelligence

Actively monitor intelligence feeds for threat or vulnerability advisories from government, trusted partners, open sources, and commercial entities. Cyber threat intelligence can include threat landscape reporting, threat actor profiles and intents, organizational targets and campaigns, as well as more specific threat indicators and courses of action. Ingest cyber threat indicators and integrated threat feeds into a SIEM, and use other defensive capabilities to identify and block known malicious behavior. Threat indicators can include:

Atomic indicators, such as domains and IP addresses, that can detect adversary infrastructure and tools

Computed indicators, such as Yara rules and regular expressions, that detect known malicious artifacts or signs of activity

Patterns and behaviors, such as analytics that detect adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs)

Atomic indicators can initially be valuable to detect signs of a known campaign. However, because adversaries often change their infrastructure (e.g., watering holes, botnets, C2 servers) between campaigns, the “shelf-life” of atomic indicators to detect new adversary activity is limited. In addition, advanced threat actors

7 EO 14028, Sec. 7. *Improving Detection of Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities and Incidents on Federal Government Networks *

8 NIST SP 800-92: Guide to Computer Security Log Management

9 E0 14028, Sec. 8. Improving the Federal Government’s Investigative and Remediation Capabilities

might leverage different infrastructure against different targets or switch to new infrastructure during a campaign when their activities are detected. Finally, adversaries often hide in their targeted environments, using native operating system utilities and other resources to achieve their goals. For these reasons, agencies should use patterns and behaviors, or adversary TTPs, to identify malicious activity when possible. Although more difficult to apply detection methods and verify application, TTPs provide more useful and sustainable context about threat actors, their intentions, and their methods than atomic indicators alone. The MITRE ATT&CK® framework documents and explains adversary TTPs in detail making it a valuable resource for network defenders.10

Sharing cyber threat intelligence is a critical element of preparation. FCEB agencies are strongly encouraged to continuously share cyber threat intelligence—including adversary indicators, TTPs, and associated defensive measures (also known as “countermeasures”)— with CISA and other partners. The primary method for sharing cyber threat information, indicators, and associated defensive measures with CISA is via the Automated Indicator Sharing (AIS) program. 11 FCEB agencies should be enrolled in AIS. If the agency is not enrolled in AIS, contact CISA for more information.12 Agencies should use the Cyber Threat Indicator and Defensive Measures Submission System—a secure, web-enabled method—to share with CISA cyber threat indicators and defensive measures that are not applicable or appropriate to share via AIS. 13

Active Defense

FCEB agencies with advanced defensive capabilities and staff might establish active defense capabilities—such as the ability to redirect an adversary to a sandbox or honeynet system for additional study, or “dark nets”—to delay the ability of an adversary to discover the agency’s legitimate infrastructure. Network defenders can implement honeytokens (fictitious data objects) and fake accounts to act as canaries for malicious activity. These capabilities enable defenders to study the adversary’s behavior and TTPs and thereby build a full picture of adversary capabilities.

Communications and Logistics

Establish local and cross-agency communication procedures and mechanisms for coordinating major incidents with CISA and other sharing partners and determine the information sharing protocols to use (i.e., agreed-upon standards). Define methods for handling classified information and data, if required. Establish communication channels (chat rooms, phone bridges) and method for out-of-band coordination.14

Operational Security (OPSEC)

Take steps to ensure that IR and defensive systems and processes will be operational during an attack, particularly in the event of pervasive compromises—such as a ransomware attack or one involving an aggressive attacker that may attempt to undermine defensive measures and distract or mislead defenders. These measures include:

- Segmenting and managing SOC systems separately from the broader enterprise IT systems,

10 See Best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping Framework for guidance on using ATT&CK to analyze and report on cybersecurity threats.

11 CISA Automated Indicator Sharing

12 CISA Automated Indicator Sharing

13 DHS CISA Cyber Threat Indicator and Defensive Measure Submission System

14NIST SP 800-47 Rev. 1: Managing the Security of Information Exchanges

Managing sensors and security devices via out-of-band means,

Notifying users of compromised systems via phone rather than email,

Using hardened workstations to conduct monitoring and response activities, and

Ensuring that defensive systems have robust backup and recovery processes.

Avoid “tipping off” an attacker by having processes and systems to reduce the likelihood of detection of IR activities (e.g., do not submit malware samples to a public analysis service or notify users of potentially comprised machines via email).

Technical Infrastructure

Implement capabilities to contain, replicate, analyze, reconstitute, and document compromised hosts; implement the capability to collect digital forensics and other data. Establish secure storage (i.e., only accessible by incident responders) for incident data and reporting. Provide means for collecting forensic evidence, such as disk and active memory imaging, and means for safely handling malware. Obtain analysis tools and sandbox software for analyzing malware. Implement a ticketing or case management system that captures pertinent details of:

Anomalous or suspicious activity, such as affected systems, applications, and users;

Activity type;

Specific threat group(s);

Adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) employed; and

Impact.

Detect Activity

Leverage threat intelligence to create rules and signatures to identify the activity associated with the incident and to scope its reach. Configure tools and analyze logs and alerts. Look for signs of incident activity and potentially related information to determine the type of incident, e.g., malware attack, system compromise, session hijack, data corruption, data exfiltration, etc.

See Appendix C for a checklist for preparation activities.

Detection & Analysis

The most challenging aspect of the incident response process is often accurately detecting and assessing cybersecurity incidents: determining whether an incident has occurred and, if so, the type, extent, and magnitude of the compromise within cloud, operational technology (OT), hybrid, host, and network systems. To detect and analyze events, implement defined processes, appropriate technology, and sufficient baseline information to monitor, detect, and alert on anomalous and suspicious activity. Ensure there are procedures to deconflict potential incidents with authorized activity (e.g., confirm that a suspected incident is not simply a network administrator using remote admin tools to perform software updates). As the U.S. government’s lead for asset response, CISA will partner with affected agencies in all aspects of the detection and analysis process.

Detection & Analysis Activities

Declare Incident

Declare an incident by reporting it to CISA at https://www.us-cert.cisa.gov/ and alerting agency IT leadership to the need for investigation and response. CISA can assist in determining the severity of the incident and whether it should be declared a major incident. Note: FCEB agencies must promptly report all cybersecurity incidents, regardless of severity, to CISA

Determine Investigation Scope

Use available data to identify the type of access, the extent to which assets have been affected, the level of privilege attained by the adversary, and the operational or informational impact. Discover associated malicious activity by following the trail of network data; discover associated host-based artifacts by examining host, firewall, and proxy logs along with other network data, such as router traffic. Initial scoping of an incident to determine adversarial activity may include analyzing results from:

An automated detection system or sensor;

A report from a user, contractor, or thirdparty information and communication technologies (ICT) service provider; or

An incident report or situational awareness update from other internal or external organizational components.

Collect and Preserve Data

Collect and preserve data for incident verification, categorization, prioritization, mitigation, reporting, and attribution. When necessary and possible, such information should be preserved and safeguarded as best evidence for use in any potential law enforcement investigation. Collect data from the perimeter, the internal network, and the endpoint (server and host). Collect audit, transaction, intrusion, connection, system performance, and user activity logs. When an endpoint requires forensic analysis, capture a memory and disk image for evidence preservation. Collect evidence, including forensic data, according to procedures that meet all applicable policies and standards and account for it in a detailed log that is kept for all evidence. For more information, see NIST Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, SP 800-61 r2. 15 Extract all relevant threat information (atomic, computed, and behavioral indicators and countermeasures) to share with IR teams and with CISA.

Perform Technical Analysis

Develop a technical and contextual understanding of the incident. Correlate information, assess anomalous activity against a known baseline to determine root cause, and document adversary TTPs to enable prioritization of the subsequent

16 NIST SP 800-61 Rev. 2: Computer Security Incident Handling Guide

response activities. The goal of this analysis is to examine the breadth of data sources throughout the environment to discover at least some part of an attack chain, if not all of it. As information evolves and the investigation progresses, update the scope to incorporate new information.

Correlate Events and Document Timeline

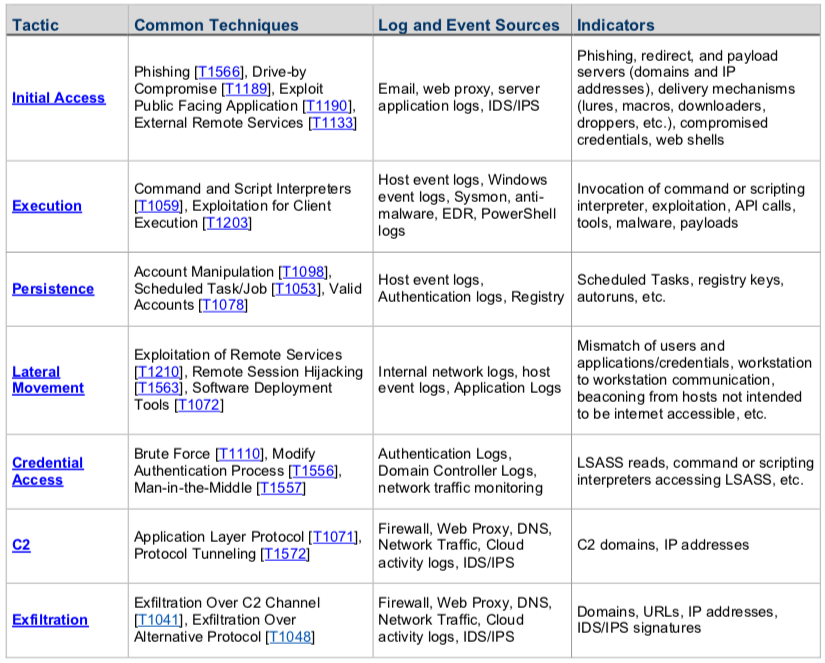

Acquire, store, and analyze logs to correlate adversarial activity. Table 1 presents an example of logs and event data that are commonly employed to detect and analyze attacker activities.16,17 A simple knowledge base should be established for reference during response to the incident. Thoroughly document every step taken during this and subsequent phases. Create a timeline of all relevant findings. The timeline will allow the team to account for all adversary activity on the network and will assist in creating the findings report at the conclusion of the response.

Identify Anomalous Activity

Assess and profile affected systems and networks for subtle activity that might be adversary behavior. Adversaries will often use legitimate, native operating system utilities and scripting languages once they gain a foothold in an environment to avoid detection. This process will enable the team to identify deviations from the established baseline activity and can be particularly important in identifying activities such as attempts to leverage legitimate credentials and native capabilities in the environment.

Identify Root Cause and Enabling Conditions

Attempt to identify the root cause of the incident and collect threat information that can be used in further searches and to inform subsequent response efforts. Identify the conditions that enabled the adversary to access and operate within the environment. These conditions will inform triage and post-incident activity. Assess networks and systems for changes that may have been made to either evade defenses or facilitate persistent access.

Gather Incident Indicators

Identify and document indicators that can be used for correlative analysis on the network. Indicators can provide insight into the adversary’s capabilities and infrastructure. Indicators as standalone artifacts are valuable in the early stages of incident response.

Analyze for Common Adversary TTPs

Compare TTPs to adversary TTPs documented in ATT&CK and analyze how the TTPs fit into the attack lifecycle. TTPs describe “why,” “what,” and “how.” Tactics describe the technical objective an adversary is trying to achieve (“why”), techniques are different mechanisms they use to achieve it (“what”), and procedures are exactly how the adversary achieves a specific result (“how”). Responding to TTPs enables defenders to hypothesize the adversary’s most likely course of action. Table 1 provides some common adversary techniques that should be investigated.18

Validate and Refine Investigation Scope

Using available data and results of ongoing response activities, identify any additional potentially impacted systems, devices, and associated accounts. From this information, new indicator of compromise (IOCs) and TTPs might be identified that can provide further feedback into detection tools. In this way, an incident is scoped over time. As information evolves, update and communicate the scope to all stakeholders to ensure a common operating picture. Note: see Key Questions to Answer for guidance.

16 Derived from the MITRE ATT&CK® Framework. Note: this table is a representative sampling of common tactics, techniques, and related logs, and is not intended to be complete.

17 EO 14028, Sec. 8. *Improving the Federal Government’s Investigative and Remediation Capabilities *

18 See Best Practices for MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping Framework for guidance on mapping TTPs to ATT&CK to analyze and report on cybersecurity threats.

Key Questions to Answer

What was the initial attack vector? (i.e., How did the adversary gain initial access to the network?)

How is the adversary accessing the environment?

Is the adversary exploiting vulnerabilities to achieve access or privilege?

How is the adversary maintaining command and control?

Does the actor have persistence on the network or device?

What is the method of persistence (e.g., malware backdoor, webshell, legitimate credentials, remote tools, etc.)?

What accounts have been compromised and what privilege level (e.g., domain admin, local admin, user account, etc.)?

What method is being used for reconnaissance? (Discovering the reconnaissance method may provide an opportunity for detection and to determine possible intent.)

Is lateral movement suspected or known? How is lateral movement conducted (e.g., RDP, network shares, malware, etc.)?

Has data been exfiltrated and, if so, what kind and via what mechanism?

Table 1: Example Adversary Tactics, Techniques, and Relevant Log and Event Data

Third-Party Analysis Support (if needed):

For potentially major incidents, agencies needing assistance can reach out to CISA. Each FCEB agency has a Federal Network Authorization (FNA) on file with CISA to enable incident response and hunt assistance. When seeking outside assistance, the default first action by the impacted agency should be to activate their standing FNA and request CISA assistance. Based on availability, CISA may provide a threat hunting team to assist.19 CISA may collaborate with other agencies—such as the National Security Agency (NSA) or U.S. Cyber Command—to provide expertise or supplement CISA’s capabilities.

Agencies may also bring on a third-party IR service provider to assist. Such providers supplement rather than replace the assistance provided by CISA. The NSA National Cyber Assistance Program (NSCAP)20 provides a list of accredited IR providers. An FCEB agency using third-party assistance is responsible for coordinating with CISA and facilitating access during the incident response, including access to externally hosted systems.

Adjust Tools:

The IR team should use its developing understanding of the adversary’s TTPs to modify tools to slow the pace of the adversarial advance and increase the likelihood of detection. The focus should be on preventing and detecting tactics— such as execution, persistence, credential access, lateral movement, and command and control—to minimize the likelihood of exfiltration and/or operational or informational impact. IOC signatures can be incorporated into prevention and detection tools to impose temporary operational cost upon the adversary and assist with scoping the incident. However, the adversary can introduce new tools to the network and/or modify existing tools to subvert IOC-centric response mechanisms.

19 Level of CISA analysis support will be determined by resources available and priority of incident.

20 National Security Agency (NSA) National Security Cyber Assistance Program

Containment

Containment is a high priority for incident response, especially for major incidents. The objective is to prevent further damage and reduce the immediate impact of the incident by removing the adversary’s access. The particular scenario will drive the type of containment strategy used. For example, the containment approach to an active sophisticated adversary using fileless malware will be different than the containment approach for ransomware.

Considerations

When evaluating containment courses of action, consider:

Any additional adverse impacts to mission operations, availability of services (e.g., network connectivity, services provided to external parties),

Duration of the containment process, resources needed, and effectiveness (e.g., full vs. partial containment; full vs. unknown level of containment), and

Any impact on the collection, preservation, securing, and documentation of evidence.

Some adversaries may actively monitor defensive response measures and shift their methods to evade detection and containment. Defenders should therefore develop as complete a picture as possible of the attacker’s capabilities and potential reactions to avoid “tipping off” the adversary. Containment is challenging because defenders must be as complete as possible in identifying adversary activity, while considering the risk of allowing the adversary to persist until the full scope of the compromise can be determined. Containment activities for major incidents should be closely coordinated with CISA.

Containment Activities

Implement short-term mitigations to isolate threat actor activity and prevent additional damage from the activity or pivoting into other systems.

Key containment activities include:

Isolating impacted systems and network segments from each other and/or from non-impacted systems and networks. If this is needed, consider the mission or business needs and how to provide services so missions can continue during this phase to the extent possible.

Capturing forensic images to preserve evidence for legal use (if applicable) and further investigation of the incident.

Updating firewall filtering.

Blocking (and logging) of unauthorized accesses; blocking malware sources.

Closing specific ports and mail servers or other relevant servers and services.

Changing system admin passwords, rotating private keys, and service/application account secrets where compromise is suspected and revocation of privileged access.

Directing the adversary to a sandbox (a form of containment) to monitor the actor’s activity, gather additional evidence, and identify attack vectors. Note: this containment activity is limited to advanced SOCs with mature capabilities.

Ensure that the containment scope encompasses all related incidents and activity—especially all adversary activity. If new signs of compromise are found, return to the technical analysis step to rescope the incident. Upon successful containment (i.e., no new signs of compromise), preserve evidence for reference or law enforcement investigation, adjust detection tools, and move to eradication and recovery.

Eradication & Recovery

The objective of this phase is to allow the return of normal operations by eliminating artifacts of the incident (e.g., remove malicious code, re-image infected systems) and mitigating the vulnerabilities or other conditions that were exploited. Before moving to eradication, ensure that all means of persistent access into the network have been accounted for, that the adversary activity is sufficiently contained, and that all evidence has been collected. This is often an iterative process. It may also involve hardening or modifying the environment to protect targeted systems if the root cause of the intrusion and/or initial access vector is known. It is possible that eradication and recovery actions can be executed simultaneously. Note: coordinate with ICT service providers, commercial vendors, and law enforcement prior to the initiation of eradication efforts.

Execute Eradication Plan

Take actions to eliminate all evidence of compromise and prevent the threat actor from maintaining a presence in the environment. Ensure evidence has been preserved as necessary. Threat actors often have multiple persistent backdoor accesses into systems and networks and can hop back into ‘clean’ areas if eradication is not well orchestrated and/or not stringent enough. Therefore, eradication plans should be well formulated and coordinated before execution. If the adversary exploited a specific vulnerability, initiate the Vulnerability Response Playbook below to address the vulnerability during eradication activities.

Eradication Activities

Remediating all infected IT environments (e.g., cloud, OT, hybrid, host, and network systems).

Reimaging affected systems (often from ‘gold’ sources), rebuilding systems from scratch.

Rebuilding hardware (required when the incident involves rootkits).

Replacing compromised files with clean versions.

Installing patches.

Resetting passwords on compromised accounts.

Monitoring for any signs of adversary response to containment activities.

Developing response scenarios for threat actor use of alternative attack vectors.

Allowing adequate time to ensure all systems are clear of all possible threat actor persistence mechanisms (backdoors, etc.) as adversaries often use more than one mechanism.

After executing the eradication plan, continue with detection and analysis activities to monitor for any signs of adversary re-entry or use of new access methods. If adversary activity is discovered after completion of eradication efforts, contain the activity, and return to technical analysis until the true scope of the compromise and initial infection vectors are identified. If no new adversary activity is detected, enter the recovery phase.

Recover System(s) and Services

Restore systems to normal operations and confirm that they are functioning normally. The main challenges of this phase are confirming that remediation has been successful, rebuilding systems, reconnecting networks, and recreating or correcting information.

Recovery Actions21

Reconnecting rebuilt/new systems to networks.

Tightening perimeter security (e.g., firewall rulesets, boundary router access control lists) and zero trust access rules.

21 See NIST SP 800-184: Guide for Cybersecurity Event Recovery for additional guidance.

Testing systems thoroughly, including security controls.

Monitoring operations for abnormal behaviors.

A key aspect to the recovery is to have enhanced vigilance and controls in place to validate that the recovery plan has been successfully executed and that no signs of adversary activity exist in the environment. To validate that normal operations have resumed, consider performing an independent test or review of compromise/response-related activity. To help detect related attacks, review cyber threat intelligence (including network situational awareness), and closely monitor the environment for evidence of threat actor activity.

Post-Incident Activities

The goal of this phase is to document the incident, inform agency leadership, harden the environment to prevent similar incidents, and apply lessons learned to improve the handling of future incidents.

Adjust Sensors, Alerts, and Log Collection

Add enterprise-wide detections to mitigate against adversary TTPs that were successfully executed during the incident. Identify and address “blind spots” to ensure adequate coverage moving forward. Closely monitor the environment for evidence of persistent adversary presence. Advanced SOCs should consider emulating adversary TTPs to ensure recently implemented countermeasures are effective in detecting or mitigating the observed activity. This testing should be closely coordinated with a blue team to ensure that they are not mistaken for true adversary activity.

Finalize Reports

Provide post-incident updates as required by law and policy.22 Work with CISA to provide required artifacts, close the ticket, and/or take additional response action.

Perform Hotwash

Conduct a lessons-learned analysis to review the effectiveness and efficiency of incident handling. Capture lessons learned, initial root cause, problems executing courses of action, and any missing policies and procedures.

The primary objectives for the analysis include:

Ensuring root-cause has been eliminated or mitigated.

Identifying infrastructure problems to address.

Identifying organizational policy and procedural problems to address.

Reviewing and updating roles, responsibilities, interfaces, and authority to ensure clarity.

Identifying technical or operational training needs.

Improving tools required to perform protection, detection, analysis, or response actions.

22 CISA Federal Incident Notification Guidelines

Coordination

Coordination is foundational to effective incident response. It is critical that the FCEB agency experiencing the incident and CISA coordinate early and often throughout the response process. It is also important to understand that some agencies have special authorities, expertise, and information that are extremely beneficial during an incident. This section highlights these aspects of coordination.

Coordination with CISA

Cyber defense capabilities vary widely. For this reason, coordinating involves different degrees of engagement between the affected agency and CISA. As a baseline, every cybersecurity incident affecting an FCEB agency must be reported to CISA. For organizations with mature security operations efforts, reporting and information sharing are key to assisting others.

Agencies also leverage CISA’s cyber defense services to supplement their own IR capabilities. CISA provides a variety of services, such as threat hunting, analytics, malware analysis, and CTI, that can help agencies throughout the IR lifecycle. The full list of cybersecurity services available to the FCEB are listed in the CISA Services Catalog, page 18.23

Reporting requirements for FCEB agencies are defined by FISMA and actioned by CISA. See the numbered circles in Figure 2 for reporting and coordination activities that should be a part of the IR process. See Appendix B, #11, for a companion checklist to track coordination activities to completion.

Figure 2: Numbered IR Coordination Activities

Figure 2: Numbered IR Coordination Activities

23 CISA Services Catalog, First Edition: Autumn 2020

It is essential for the affected department or agency to closely collaborate and coordinate with CISA on each step in the IR flow chart. Some of the essential coordination and communication activities are defined by the numbered circles. Each number corresponds to a description below:

1) Inform and Update CISA

The FCEB agency provides situational awareness reports to CISA, including:

Notifying CISA within 1 hour of incident determination as directed by OMB M-20- 04. Note: FCEB ICT Service providers should provide notification of cyber incidents in accordance with FCEB Agency Contracting Officer (CO) requirements, which include National Security System (NSS) reporting requirements.24

Where applicable, notifying their appropriate Congressional Committees, their Office of Inspector General (OIG), and OMB Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer (OFCIO) as directed by OMB M-20-04.

Providing incident updates to CISA as appropriate until all eradication activities are complete or until CISA agrees with the FCEB agency that the incident is closed.

Complying with additional reporting requirements for major incidents as mandated by OMB and other federal policy.25

2) CISA Provides Incident Tracking and NCISS Rating

Within one hour of receiving the initial report, CISA provides the agency with (1) a tracking number for the incident and (2) a risk rating based on the CISA National Cyber Incident Scoring System (NCISS) score.26, 27

3) Share IOCs, TTPs, data

The affected FCEB agency share relevant log data, cyber threat indicators with associated context (including associated TTPs, if available), and recommended defensive measures with CISA and sharing partners. Sharing additional threat information is a concurrent process throughout the containment phase. Incident updates include the following:

Updated scope

Updated timeline (findings, response efforts, etc.)

New indicators of adversary activity

Updated understanding of impact

Updated status of outstanding efforts

Estimation of time until containment, eradication, etc.

4) CISA Shares Coordinated Cyber Intelligence

CISA—in coordination with the intelligence community and law enforcement—shares related cyber intelligence to involved organizations.

5) Report to Federal Law Enforcement

The FCEB agency reports incidents to federal law enforcement as appropriate.

6) CISA Determines Escalation

CISA or the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) determines if the incident warrants Cyber Unified Coordination Group (C-UCG) escalation, and, if so, recommends establishment of a C-UCG in accordance with the provisions of PPD-41 § V.B.b. C-UCG is the primary mechanism for

24 EO 14028, Sec. 2. Removing Barriers to Sharing Threat Information

25 Per OMB M-20-04, appropriate analysis of whether the incident is a major incident will include the agency CIO, CISO, mission or system owners, and, if it is a breach, the Senior Agency Official for Privacy (SAOP). Regardless of the internal reporting chain of the organization, CISA must receive the major incident report within 1 hour of major incident declaration.

26 CISA Federal Incident Notification Guidelines

27 OMB M-20-04

coordination between and among federal agencies in response to a significant cyber incident as well as for integration of private sector partners into incident response efforts.

7) Provide Final Incident Report

The FCEB agency provides CISA post-incident updates as required.

8) CISA Conducts Verification and Validation

To ensure completion of recovery, CISA will validate agency incident and vulnerability response results and processes. Validation assures agencies that they are meeting baseline standards, implementing all important steps, and have fully eradicated an incident or vulnerability. For all incidents that require the use of the playbook, agencies must proactively provide completed incident response checklists and a completed incident report to close the ticket. If an agency is unable to complete the checklist, the agency will confer with CISA to ensure all appropriate actions have been taken. CISA will evaluate these materials and:

Determine that the incident is adequately addressed, and close the CISA ticket.

Determine if additional response actions must be completed and request the agency complete them prior to closing the ticket.

Request more information, including log data and technical artifacts.

Recommend the use of CISA or other third-party incident response services.

Affected FCEB entities must take CISA-required actions prior to closing the incident. Working with affected FCEB entities, CISA determines the actions, which vary depending on the nature of the incident and eradication.

Intergovernmental Coordination

In a broader context, FCEB cyber defensive operations are not alone in tackling major incidents. Several government departments and agencies have defined roles and responsibilities and are coordinating across the government even before incidents occur. These roles and responsibilities can be described in terms of concurrent lines of effort (LOEs): asset response, threat response, intelligence support, and affected agency response; together these LOEs ensure a comprehensive response. Table 2 summarizes the LOEs for agencies in responding to cyber security incidents.

Table 2: Federal Government Leads for Lines of Effort per the NCIRP28

28 National Cyber Incident Response Plan

For major incidents or incidents that may become major, CISA is the “front door” for agencies for asset response. CISA will work with affected FCEB agencies to determine their needs, provide recommendations for services, and coordinate with other agencies (e.g., NSA) to provide a whole-ofgovernment response. By serving as a single coordination point, CISA can ease the burden on FCEB agencies by facilitating the assistance available across the government.

Depending on the nature of events and involved organizations, FCEB agencies may also work directly with other LOE lead agencies in support of those LOEs. Figure 3 identifies the organizations providing the types of data and information that inform incident detection, analysis, and response.

The whole-of-government roles and responsibilities are outlined in Appendix G.

Figure 3: Whole of Government Asset Response

Table of Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- INCIDENT RESPONSE PLAYBOOK

- VULNERABILITY RESPONSE PLAYBOOK

- APPENDIX A - KEY TERMS

- APPENDIX B - INCIDENT RESPONSE CHECKLIST

- APPENDIX C - INCIDENT RESPONSE PREPARATION CHECKLIST

- APPENDIX E - VULNERABILITY AND INCIDENT CATEGORIES

- APPENDIX F - SOURCE TEXT

- APPENDIX G - WHOLE-OF-GOVERNMENT ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES